2. To Body By Breath (part I)

Oct 25, 2024

“I’m afraid of the Dark. You, who walk so cheerfully, whistling your way, stand still for five minutes. Stand still in the Dark in a field or down a track. It’s then you know you’re there on sufferance. The Dark only lets you take one step at a time. Step and the Dark closes round your back. In front, there is no space for you until you take it. Darkness is absolute. Walking in the dark is like swimming under water except you can’t come up for air.”

—Jeanette Winterson, The Passion

The most impactful gross examination, the one that has inspired me toward this epic journey of human dissection and hundreds of hours in anatomy labs, has been the one taking place in my very own living body. I was twenty-six when the need for introspection and healing coaxed me—kicking and screaming—into the unfamiliar world of emotional metabolism. My main dissection tools, before I met a real scalpel, were my very own body and breath.

Ottawa, Ontario: “It was raining on Parliament Hill as Queen Elizabeth II and Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau signed the Proclamation of the Constitution Act on April 17, 1982. Marks left by the raindrops as they smudged the ink can still be seen as physical reminders of the rich history of the act.”

—Library and Archives Canada

I remember the rain that day, it was a Saturday. I was nine years old and had gone to my ballet teacher’s house to rehearse for my role as Cinderella in our upcoming recital. I was called home early and recall happily skipping through the puddles and around the worms bathing in the wet of the sidewalks on the short journey home. I’ve always loved the rain.

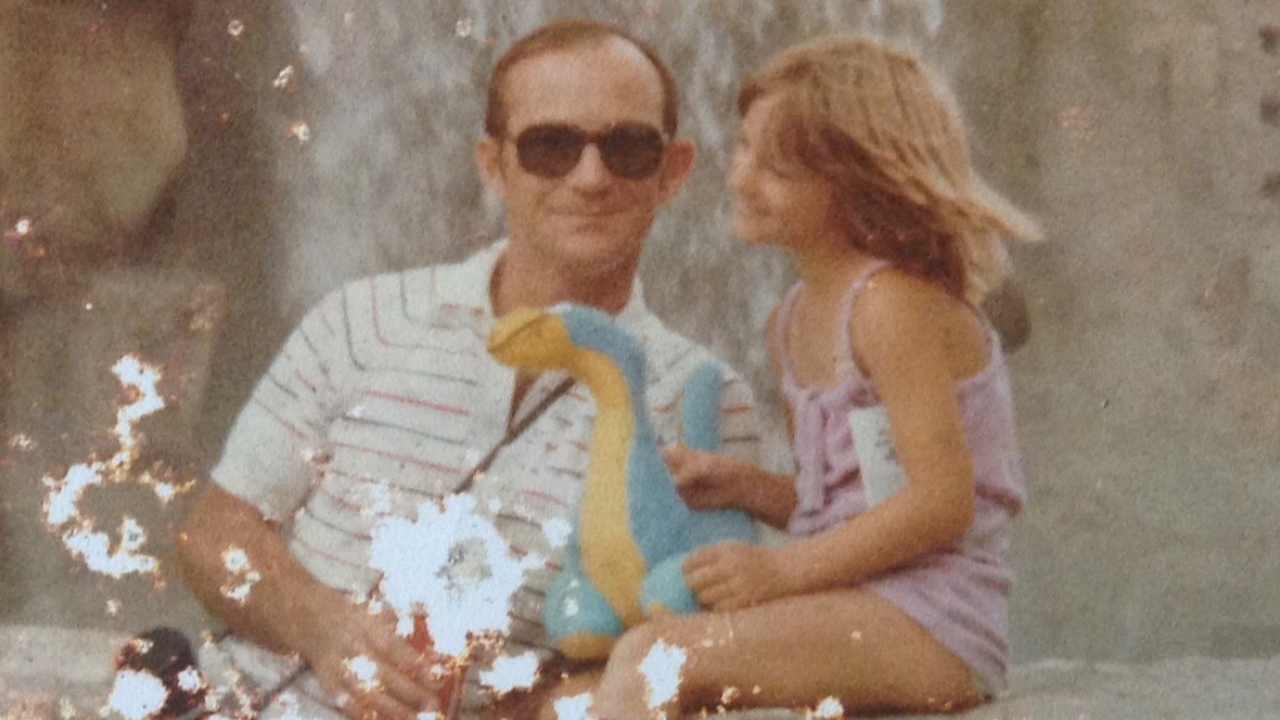

My father had left the house that morning to take pictures of the Queen, as history was being made on Parliament Hill. He didn’t make it far before a cardiac arrhythmia stopped his heart.

I arrived to find my mother on the couch in the basement, her best friend at her side. She had obviously been crying, something I don’t think I had never seen. In her hand was a crumpled tissue. The entire scene confused me. I don’t know why they were in the basement—that was the rec room, not generally used during daytime hours, and why was her friend there?

I immediately burst into tears, wrapping my arms around my mother, but I was deeply confused. I knew what had happened was serious, given the mood in the room, but had to piece it together for myself. I didn’t quite understand what my mother meant when she said my dad had “collapsed at the wheel.” I pictured him slumped over the front tire of his little red pinto while changing a flat in the parking lot of our garden home condominium. That is not what had happened. His heart stopped, instantly terminating his life while driving. He coasted through a red light without incident and came to a stop where some passersby pulled him from the car to perform CPR. I have no idea how I know this detail, or if it’s even true.

Up until that moment, my life had been an orchestrated symphony of tasks and events. My dad tucked me in at night and my mom got me to school in the morning. There were ballet classes for me and, for my brothers, sporting events coached by my dad. We spent weekends with our closest family friends at a campground an hour out of the city. Dad worked full-time as an x-ray technician in the basement of a medical building downtown. My mom, a registered nurse, worked overnights twice a week at a nearby hospital. We lived the picture-perfect family life.

As our house began to swell with friends and family members, an uncomfortable energy I was not familiar with slowly infiltrated the environment. My dad was thirty-nine, one year older than my mother. The overarching feeling among the adults was that of collective heartbreak and tragedy—but there was something else too. There was a feeling of awkwardness that went beyond the shock and grief. An air of something forbidden that should not be mentioned. I wouldn’t learn until more than a decade later that my parents’ marriage had been crumbling at the time of my dad’s death. Their secret was quietly spilling out as my mother attempted to recalibrate amidst the finality of having to forcibly suffer the termination of a life, a relationship—a possible reconciliation—to sudden death. As an adult, I am led to believe that even my mother’s closest friends had not been privy to this information until those surreal days around which time stood still.

I couldn’t understand why when I entered a room undetected, the atmosphere was heavy, tragic and paralyzed, but if my presence was noticed, the shift was immediate to something superficial, maybe even funny, awkwardly so. My instinct was to escape, to protect myself from the emptiness of being alone in a room full of people. My brothers had already left the house to join the neighborhood kids in the courtyard, and I figured the only place I could be truly alone was in the bathtub. Already an introvert, my world began to get smaller and smaller as the people around me were unavailable for my suffering.

The days surrounding the death, wake and funeral were full of friends and family members tending to the details of ceremony and assisting my mother in whatever affairs needed to be ordered. For example, they were intent on getting me to the mall and into a pair of shoes that would match my funeral dress. I don’t recall anyone relating to me on an emotional level. Everyone rallied around the superficial practicalities and there was no mention of grief. No warning that my brothers and I would spend the rest of our lives trying to figure out how to mourn our loss. It may not have been my first lesson in emotional avoidance, but it was certainly the most profound. It felt like it was all a business transaction that left no room for vulnerability. Faces were put on and the task at hand was to move forward as if it was another day, and not the devastating loss from which healing would be required.

As young as I was, there was no clear option for me to do anything but follow suit, so I learned quickly how to keep the world at arm’s length and stifle my pain. The adults around me modeled this behavior. If any of them were grieving, no one was letting on.

Our family never spoke of my father again.

I was not aware that this was an unhealthy response, and without argument, adopted this example. Shortly after the funeral, our house cleared of friends and relatives. The kitchen was a clutter of empty casserole dishes and cake pans to be reclaimed by their owners. In those days the rotary-dial telephone that was affixed to the wall still rang for Mr. Anderson. I would freeze at the caller’s request to speak with him, while shamefully passing the receiver to my mother for her to manage the awkward exchange that would follow. I couldn’t bring myself to say it for her, but I wanted to. My instinct to protect those around me from pain was far beyond the skill of my young years.

My cousin was a toddler when my dad died, but she remembered him and could name him from the photo that sat on the mantel in our grandparents’ living room. I became almost obsessed with pulling it off the shelf and asking her to identify everyone in the picture because she was the only one willing to say his name, and I needed to hear it. At social gatherings the adults in my family hid their vulnerabilities behind a cribbage board and the next hand of cards. I could be found in the living room, chest open massaging my heart, training it to beat on. My small cousin had no inkling she was helping me to keep the dead family member in the photo alive. Her newfound voice enunciated again and again “Uncle Bob,” proud of her success and oblivious to my pain. The word Dad had already become a title that belonged only to other families. Writing about it now feels like narrating someone else’s distant, emotionless story. Over the following eight years, three more faces would fade from that photo: both of my mother’s parents and her brother, my little cousin’s dad. Fewer card nights, for lack of players, more walls and greater distance. Eventually the photo would also disappear from the mantel.

Intellectually I think my lab visits are about deeper learning, and that is true, but maybe the deeper learning is really about life and death—not anatomy. Maybe my incessant need to look into the body has been ruled by the inappropriate silence surrounding the death of my father.

My life was divided into before and after.

In the immediate after, my mother increased her working hours to full-time, twelve-hour shifts night and day. Suddenly my brothers and I were responsible for making meals and staying on top of chores. We took turns navigating the language of food preparation, learning to fold and mince on one hand, without burning the other part of the meal on the other. I would be overcome with emotion trying to figure out how much a clove of garlic was: the whole head, a section, or a secret measurement I had no means to translate. I was terrified of getting it wrong and letting my mother down, because I knew how hard she had been working. The frustration with her lack of control over our situation would be revealed when she noticed streaks of furniture polish or glass cleaner on any surface we were tasked with maintaining. While we kids argued over whose turn it was to do the dishes or sweep the floor, she’d criticize the work we thought was already complete. The emotional climate in our house became more and more volatile as our collective pain deepened the fissures that would later become unbridgeable.

A neighbor only slightly older than us would come and stay the night so we weren’t alone—or so we wouldn’t kill one another. When the sitter called me a brat and I told my mom, instead of expressing her disgust and coming to my emotional rescue, as I had baited her to do, she simply stated that it must have been true. I was desperate for attention, and I think that was exhausting for my mother.

On another occasion after my one of my brothers hit me—we were often physical in our fights—I scratched at the red mark on my skin, determined to keep it fresh as evidence later. She said I probably deserved it. I felt like no one had my back. Feelings were discouraged and often ignored until it became clear that vulnerability was not welcome in our home. The only acceptable emotion was anger. So everyone was angry, all the time (still). We learned to use silence as a weapon, and passive aggression, although I couldn’t name it, was rampant. I was in a constant state of anxiety over what I had done wrong, as strategically placed silences infiltrated our interactions.

Comments on my report cards changed from before, when I “had a great sense of humor and was a pleasure to have in class,” to the after: “arrives unprepared. Books often left at home and homework incomplete.” It wasn’t my fault, but I didn’t know that.

One of my brothers turned the stove on high, let the element get red hot and then turned it off. He dared me to put my hand on it. I wasn’t stupid and said so, knowing I was being set up. He insisted it was not hot. I thought, I’ll show you,as I spread my fingers, opened my palm and planted it flat on the element, stamping my flesh with the spiral of the blistering coil. In a panic, he grabbed my hand, yanking my whole body along with it to the sink where he forced the cold water to run over the burn while yelling at me for being so stupid. I don’t know why he did it. I don’t know why I did it. But it relieved for a moment some deep suffering we had both been trying desperately to deny. I don’t remember if I even bothered trying to get him into trouble for it.

Grief descended upon our household silently, leaving irrevocable damage in its wake.

[I wrote this chapter in 2020 and just recently (2024) came across my Dad’s obituary and learned that he died on the15th of April—not the 17th, as I had always believed. The Queen arrived in Ottawa on the15th and he was heading out to capture her arrival, not the signing of the Declaration on Parliament HIll that would happen 2 days later. It’s freshly astonishing to me that his existence was allowed to be erased like that.]