19. Afterword

Mar 08, 2025

In the first several months of the pandemic, while struggling to acclimatize to the uncertainties that lay ahead, I began walking. It was the most effective way to fill my day. I didn’t listen to music or talk on the phone. I didn’t make eye contact with anyone along the way. For hours at a time, I put one foot in front of the other, marking a daily 10k perimeter around my centertown neighbourhood. My walk route changed from time to time, but inevitably I found myself tracing the waterways of my city and the glimpses of nature provided there. I walked until the blisters on my feet oozed with infection, but I could not bring myself to take a day off. I needed the movement, the fresh air, the distraction.

Historically, in my younger life during times of unemployment, I would use the time to nestle (wrestle) more deeply into my yoga practice. It was a tough discipline to get myself to the studio and sweat out my boredom and frustration, but I had nothing else to do, and a single class could occupy me for two hours or more—depending on how quickly my legs carried me to and from. The practice has always been a love-hate thing for me. The love was for the release of hormones and the surge of endorphins that made me feel so alive. The hate was for the anger and frustration that frequently bubbled up through my body as the heat began to rise from the physical challenge. I never knew which sensation a practice would bring—love or hate. The fear of not knowing, or not being able to control the outcome, pulled at me strongly, and it was often a fight to get myself to the studio. When I succeeded, it was because the threat of boredom was stronger than the ominous emotion that lay beneath the dullness of my life at the moment.

This fight has been ongoing for twenty-some years. The toughest were between years two and ten. How did I do that? Decades of wrestling my way through a practice I love? What do I love about it? These are difficult questions to answer. I guess it’s the lightness I feel in my body after having tangled with the demons of my emotional self. Win or lose, there is a satisfaction in having engaged. On the days I opt not to fight it out, I feel comforted by my melancholy. Like an old friend, I can snuggle up with her, allowing her weight to ground me in the stillness and rest that comes with inaction. It’s wonderful to have the relief of life’s pressures for a time. But then restlessness propels me back to my mat. The symbolic ticktock of the metronome between these two extremes has been very tiring.

I brought my practice home early on but relied greatly on the community of the studio to keep me engaged. I identified with a mostly made-up social pressure that demanded evidence of my advancement in asana, which, for the first ten years, kept at least one foot in the studio as I struggled to keep up with my peers.

Yoga destabilized me.

I realize that statement is in direct contrast to everything I have written about it until now. The pandemic has forced me to reevaluate a lot of things.

I was not emotionally stable when I first walked into the studio in 1999, but the practice put a container around the approximate edges of my instability, loaning me the strength to repair the damage of my grief.

Facing the reality of that instability knocked me down over and over, bruising my ego and embarrassing me into action. Fuck, I hate yoga, but I know it has saved (the quality of) my life.

I haven’t done a full yoga practice in months.

It’s the end of January now, and my mat has lain undisturbed in the closet since the summer. The vacuum cleaner beside it has gotten more use—but I feel great.

When I get down on the floor for a downward dog randomly during the day, I experience a delicious stretch that reaches into my fascia and travels deep beyond a single muscle. It’s a sensation I have not experienced in forever, because I’ve spent upwards of twenty years lengthening every muscle in my body to the point that I no longer felt stretch, ever. My body got stronger in response to the laxity of my joints. The postures I had to twist my body toward to evoke a physical challenge became ridiculous, but the same old practice no longer demanded my mental presence—nor did it deliver the satisfaction it once did. Now if I am inspired to complete a sun salutation, the breath—because it’s new again—is more fulfilling than I recall it ever being, but I’m not compelled to do more than two. My joints feel steadied, and that sensation is reflected in my mental and emotional state.

The exhaustion of having to continuously dust off the assault of my yoga practice has forced me to get stronger. Or is it softer? I suppose it’s something in between the two. I no longer bruise as easily, and my boundaries are more defined but also not as sharp as they once were. I feel stable for the first time in maybe…ever.

The last really focused practice I did was on day seven of the pandemic, when I labored through 108 sun salutations. In retrospect, I was desperate that day to feel the steadiness of that old container yoga had previously provided me but that had been slowly dissolving for years. Now when I engage in yoga, I feel the memory of the instability that first brought me to the practice, and it’s unsettling. When I walk, I feel the opposite. Rather than the obsessive focus on the climate within, I am appreciating the view of nature around me. I know the steadiness of my step has sprouted from my yoga practice, but I’m going to continue walking while the roots lie unseen beneath the earth for a while.

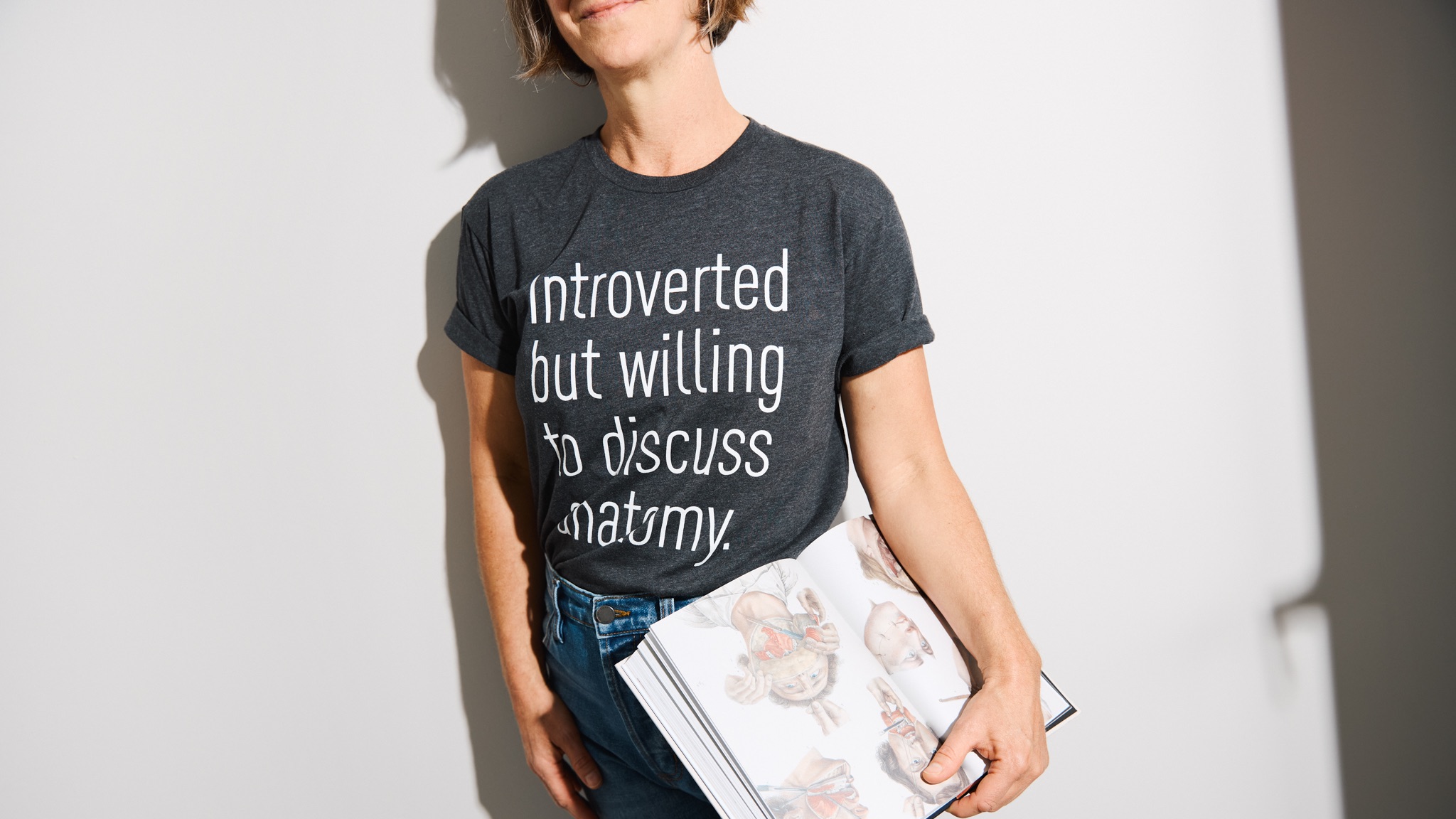

Studying anatomy allowed me to engage in a physical way with the bedrock of my existence, linking the divide between mind and body. I have been obsessed with both, and especially the elusive place where I believe they overlap.

Anatomy has brought a richness to what’s left of my asana practice—the few sun salutations I move through before work. My anatomical knowledge directs me to where I need strength if I am going to continue with massage, a career that taxes my body. I am moving and breathing from a body that has been transformed by so many years of hard, emotional work. I feel joy in my renewed relationship with asana.

And my work is now more precise in solving a client’s physical pain. The urgency to get it right has dissipated with the knowledge that the body is much wiser than me, and I long less and less for the lab. It’s such a strange place to be. Content.

The pandemic has transformed how we practice and access yoga, but that’s been changing for years. It’s changed dissection in a way that has made it accessible to anyone who is even the tiniest bit interested: log on for an hour of livestreamed dissection and enjoy lifetime access to recorded segments of Gil hosting small groups in the lab. The emotional and financial risks of not being able to stomach the smell or the gross bits have been removed by the ability to attend affordably from your own living room. It’s a fantastic bonus for humanity to see what we in the lab have held so sacred, but it doesn’t offer the privilege of holding a heart in your hands. The pandemic has changed the already watered-down ritual of death by limiting funeral gatherings and the hugs so essential to emotional repair. The pandemic has changed my relationship with stress and my body.

In the early days I desperately missed my twice-daily pilgrimage to the trails that led me on my bike commute from one end of the city to the other. My workday previously began with an hour of yoga before my coffee pit stop by the water; it was glorious to map my day around these rituals. Once the initial uncertainty of the future subsided and I began to sink into an unstructured day, I was confused by the deep feeling of rest I was experiencing in my body. Everything about my schedule supported my dependence on nurturing activity, so why was I feeling burnt out all the time? I made self-care a regimen—maybe that wasn’t the best approach.

As walking became the main event of my day, I didn’t notice the way my body knew exactly how to do it. There was no need to problem-solve where my foot should land or for how long, in order for it to be therapeutic. Walking was a constant motion that didn’t need a destination. Walking did not require me to achieve anything, and it didn’t take long for me to even care about not doing yoga.

By bike, I began exploring parts of my hometown I had never seen. Lacking familiarity with the new trails, I would ride too far and arrive home completely wrecked, but content. Endurance by foot or bike was hard-earned because the mileage, previously constrained by the distance between home and work, was now stretched by a broadening sense of adventure. It was difficult on a lot of days to get myself out of the house, but the discipline awarded by the years of yoga supported me in getting there.

Ten weeks into the first lockdown, massage therapists received permission to begin seeing clients again. But the facility that housed my office—a gym inside our local college—did not pass the guidelines that would allow me to return just yet. I waited another four weeks before making the tough choice to move my practice to a clinic only six blocks from home. My struggle in deciding was almost entirely rooted in the thought of losing my commute, which has been a blessing in disguise.

Now I am forced to get on my bike for the pure pleasure of it. I have to plan out the time and pack a lunch, just in case I ride too far. The pandemic has changed the hours the clinic is allowed to operate, and my week looks a lot different than it used to. If I want to keep walking—and I do—I have to schedule it. My body is no longer at the ready with the endurance I once had from a daily routine. I feel winded yet rested, because I’m not in constant motion anymore. I am choosing the times to insert movement, which has resulted in a joyous experience of my body. Instead of trying to cling to an old lifestyle, I have become a better listener.

Anatomy is no longer my distraction from the emotion stored in my body, as it had been when I began yoga. It is my muse. I didn’t think it possible, but having not visited the lab for my yearly refresher, I am feeling the body in even more profound ways. Instead of scanning my memory bank for images of anatomy while I work, I am feeling muscle fiber float up against the pressure of my waiting hands, where I am now more inclined to embrace the tension in order to fully understand it before deciding how best to respond.

Yoga introduced me to my body. Dissection allowed me to know it. The intersection between the mystery of where the mind and body overlap has been a study in observation and inaction.

When I massage a muscle, I want to bring my client to the experience of their body beneath the skin. If I get it right, the sensation of pressure along the ribbons of fascia and the separation of tissue—experienced simultaneously as pain and relief—calls them into the joyful sensations of embodiment. In these moments, the mind and body are so obviously intertwined. The sensation felt in the body is processed in the mind, but it’s also the other way around.

In the wise words of Gil, Anatomy is not something “other” for us to “know.” Embodiment should be the goal of this life, before we leave it behind.