12. The Sleeping Tortoise (Part II)

Jan 18, 2025

Less than a year into my yoga practice, I experienced an emotionally traumatic injury. I was receiving a strong adjustment in a pose I probably should not have even attempted. The ashtanga yoga system is well known—and criticized—for its deep, hands-on approach, but this was an aspect of the practice I adored. When my teacher moved my body into position, it could override what my mind thought I was capable of and take me to deeper levels of understanding. The physical touch was something I was not receiving anywhere else, and it opened me emotionally toward comfort with intimacy.

I had no idea a body could break like that.

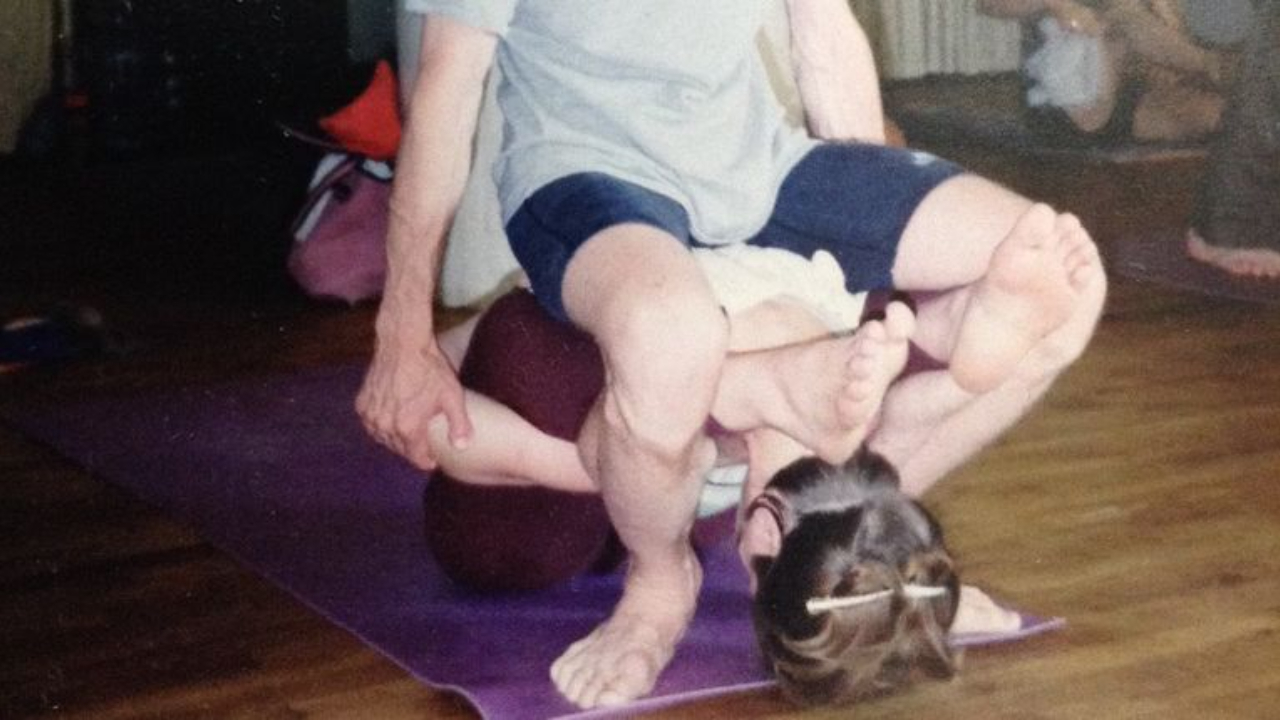

The asana was supta kurmasana, or sleeping tortoise. In this position, the legs bend up around the shoulders with the ankles crossed behind the neck. The arms wrap around the thighs to clasp behind the lower back. I thought I had the flexibility to move my hips in that way, but my long spine and short limbs made it a tight squeeze for me. My teacher was putting pressure against my legs to assist me into the tight space of my body. We had done this successfully dozens of times before, but on this day my thighs were not fully behind my shoulders, and when he applied pressure, it went straight into my collarbones. I felt an acute increase in pressure followed by a loud crunch. The forceful breach of my structure caused my teacher, who was using me for leverage, to lose balance. I thought my arm had fallen off my body. No lasting damage was done when my clavicle momentarily dislocated from its anchor at the sternum, but it was the end of my practice for six weeks while I nursed my broken body back to health. The most notable aspect of the injury was how it catapulted me into my emotional self. The flood of emotion that released in the year that followed was astonishing.

I went through bouts of undefinable sadness, followed by extreme giddiness. Launched by this physical injury into a place where I could not locate a balance between earth and sky, I knew instinctively, without tangible comprehension, that what I was experiencing was likely due to years of unexpressed emotion. After I lost my dad I remember crying only in the days immediately following, and mostly privately. I didn’t feel safe expressing my sadness beyond that, because no one else was doing it. I thought if my tears were seen, I would be judged, or make others uncomfortable, so I repressed my grief. The year that followed the injury was full of intense release. I sewed hearts onto the front of all of my yoga tops as a symbol of the reparation that needed to take place. After a year I began to wear the shirts inside out. Partially concealing the vulnerability of this lengthy healing from my peers, partially to allow the symbol to be closer to my actual heart.

In the pain, I did not find any specific answers but I did gain experience with allowing my emotions to flow with less fear and judgment. By exposing myself in this way, even if to no one other than me, I was healing some very deep wounds and finally beginning to grieve. I started to feel that the margin between physical and emotional pain, if it existed at all, was hardly perceptible.

Six years later, I would suffer another injury with a different teacher. Ironically, the asana was exactly the same as the previous one, but this time turned upside down. Yoga nidrasana (sleeping yogi): legs behind head, hands clasped at back. Resting on my back, instead of facedown. The adjustment was identical. I was being squeezed deeper with the instructor’s legs around mine as he stood over me. This time, I didn’t feel it coming, and it was my sacrum that moved. The result was “foot drop” and a deeper inquiry into my emotional self.

The unseen injuries are possibly more relevant when looking into a cadaver. I mean, looking at an old bumpy bone that healed itself from a long-ago break interests me on an intellectual level but does not catapult me to another realm in the way the bumps on Fable’s organs did. The bone makes me marvel at the intelligence of the body and how it puts itself back together in such a way that it will never break in the same spot again. The natural repair of Mobe’s fractured collarbones showed us scars that were indisputable facts of his living history. In the dissection of Fable, her mastectomy scar distorted her skin, then disappeared in the fat beneath, becoming visible again in the deep fascia. We inspected each layer as the scar wove its way through her tissues until it vanished at the layer of muscle where the surgeon’s blade ceased its cut. Emotional pain was palpable in those of us around her, yet we could not objectively find any emotion in her diseased remains.

So far there has never been need for my body to undergo any sort of medical intervention. All of my bones are intact, and I have even managed to hang on to my appendix, tonsils, and wisdom teeth. But what of the grief? What route did sadness take through my body on its long journey to the surface for healing? Is that journey traceable on the surface of—or inside—my organs? And how much of it has yet to release?

By the time we opened the viscera in the three-week lab, there was a lot of hypothesizing and speculation bouncing around the room, as we had twelve bodies to diagnose. Much of the language being used assumed that something must have been “wrong” with our donors. After all, they were dead and we were seeing a fair bit of pathology. What if what we were seeing represented health? A statement offered by Jim, a longtime lab participant.

Jim’s donor had walnut-sized lymph nodes that were the consistency of crunchy water chestnuts. A normal node is small and squishy, like a caper, and not easily found inside its cozy adipose nest. The job of the lymphatic system is to carry excess fluid from the body back into circulation. While doing this, it surveys the fluid for pathogens and initiates an immune response when one is detected. During this response, lymph nodes swell as the fluid is delayed for filtration that removes the offending substance. It is a good question to ask what is wrong with someone who died while their lymph nodes were so dense and large, but to Jim’s point, the body was doing exactly what it was supposed to. When symptoms arise, the body is responding to a deeper problem, and symptoms are an indication that healing is taking place on some level. The body may not always be able to heal itself, but you can see evidence of its efforts.

What about emotional injury? Strange things can unearth unhealed childhood trauma that has had the opportunity to incubate itself while nestled unchecked, deep in one’s psyche. How does emotion store itself in a body and does it affect the homeostasis of the environment if left to take up space meant for something else? These questions provoke deeper emotion during dissection when we come upon diseased organs. I do not know what my liver is doing at all times, but I know it is performing some really important tasks to keep my body functioning. It makes sense to me that my emotional state must influence this. I mean, if I can manifest the cold sore that inevitably shows up when I am stressed, what else can I affect?

We know that physical touch and friendship are integral to living a long, healthy life. The links between the physical and emotional are evident in all of us, yet the concept is still largely theoretical when it comes to disease. Medicine does not diagnose cirrhosis of the liver as coming from being sad, but you might be led to eat or drink yourself into disease in an attempt to escape emotion. There are studies documenting how prolonged depression can alter brain chemistry affecting the immune response to stress, increasing risk of other diseases. Other studies reveal that emotional pain shows up in the same part of the brain as physical pain, suggesting the two to be indistinguishable at the level of feeling. Pain is pain, regardless of the source.

I question whether or not the seed of sadness or addiction is already inside a person when they arrive on this earth. The esoteric quality of the question, perhaps, is what made me want to look into the grounding of our physical form.

On an emotional level, following the second injury that resulted in foot drop, I experienced, again, some of the traumas of my past. One morning after a short yoga practice, sitting on my mat, I sunk into a deep meditation that continued as I gently laid my body flat on the floor for savasana. Images of my youth held me captive in this state, as if I were watching a movie on the big screen of my mind. I saw and understood, for the first time, the events surrounding my dad’s death. I saw the adults around me changing the subject and trying to make me laugh. Was it pain I was seeing in them? I don’t know, but I was feeling my own, perhaps magnified by the fact that I was not being met on an appropriate emotional level. I recall losing my mother in a K-Mart one day, my fear building as I spun around to see she was nowhere in sight. My throat filled with tears that I tried desperately to choke back. In a panic, I went to the customer service desk to have her paged. She, I imagine, was so annoyed to hear her name called over the intercom—amused to think I believed she would leave me. We simply did not understand one another. I needed her, and I hated that. My need for her was a burden for us both.

I don’t remember how old I was, maybe ten or eleven. Thinking back, I realize this is still quite young, but I grew up quickly after my dad died, and I felt as though I was too old to be so scared. I felt that if I didn’t keep her in my sight, tether myself to her, she would leave at the first opportunity. Looking back now, this was not a ridiculous concern.

On my yoga mat, I lay still amid the memory, wondering why these images were arising now and where they had been hiding. My body had opened up, and memory was pouring out of my cells in tandem with this seemingly insignificant physical injury.

In the weeks following, I would go into an internal rage at the sound of my mother’s voice. I was waking up to just how complicated our relationship had been, and I suppose I was preparing for it to end. I had always felt that if she loved me, it was conditional. My mother was not an affectionate woman, and most of the feedback I received was in the form of criticism. In my eyes, she never missed an opportunity to let me know how I had failed at something. I became a perfectionist, ironically, as a way to disappear: if I got something right, I could fly under the radar unnoticed. It was emotionally exhausting, and I never let down my guard. That feeling of humiliation for needing her back then was now showing me how I lost my trust in her and, in a sense, all human beings around me. I didn’t feel safe or important to anyone, and I had to journey back to heal the girl I thought I once was but who had existed within me all along.

Memory is a peculiar thing, and the accuracy of my retrospection is probably tainted. I may have matured quickly into an independent woman, but my imagination remains young, fantastical, and maybe fictional. The memories built upon the pain may be cloudy, but the sensation is inarguable. Pain is pain. Is pain.

It would be another five years before my mother and I finally decided to cut ties. It’s more complicated than that for us; I have no doubt her story is just as poignant, if not more so. Perhaps one day I’ll have a better understanding. But for now, it’s my story that is healing.